Source: Bettmann / Getty

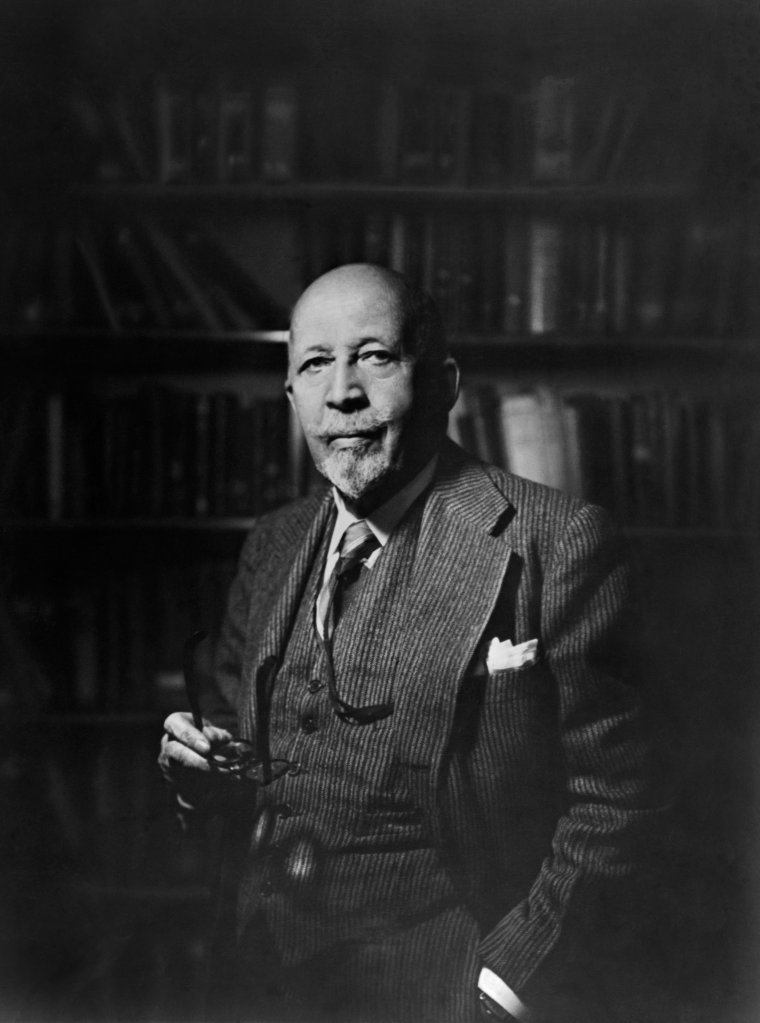

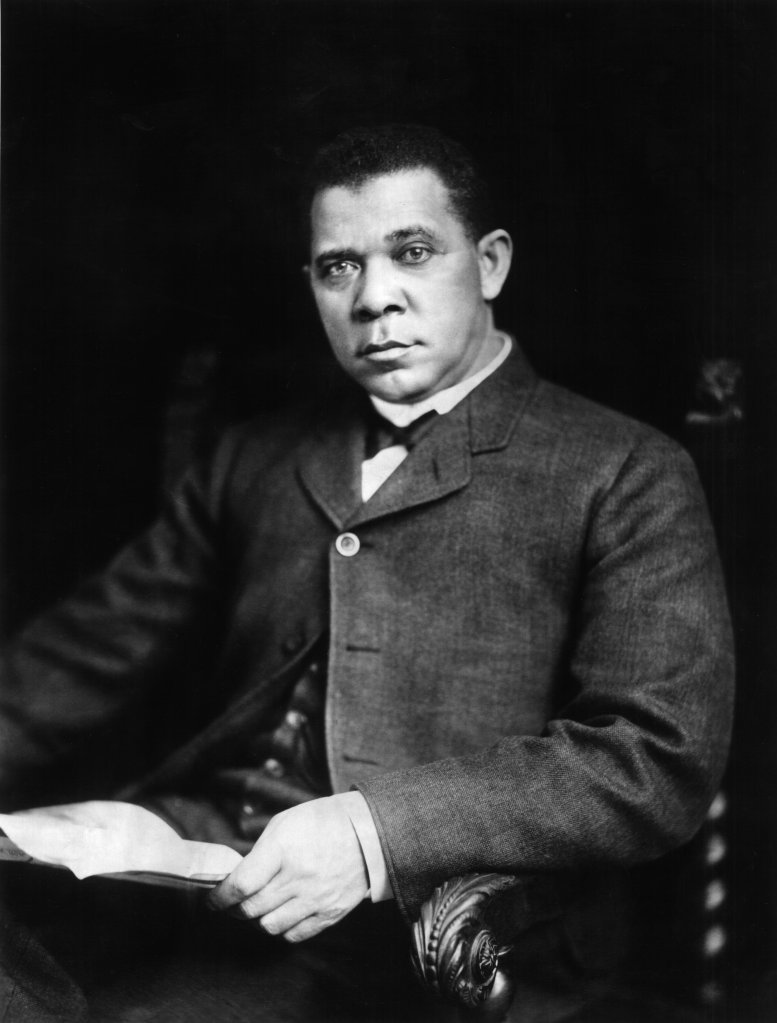

Some of our most prolific figures in Black History didn’t always see eye to eye. W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington, for example, were two men on different sides of the movement. Washington encouraged Black people to basically conform in order to be accepted by whites, while DuBois garnered a reputation for taking a more “radical” stance.

Washington, who was born a slave in Virginia and co-founded Tuskegee University, encouraged Black Southerners to look towards trades, like farming, to gain economic freedom rather than focussing on civil rights, though it’s noted that Washington was an apparent secret supporter of anti-segregation and anti-voter suppression campaigns. He became one of the leading Black voices during the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, and while some leaned towards his ideologies, others opposed his views.

His publicly conservative views and alignment with the Republican party and presidents alike, made him a nationally-known figure and popular among wealthy whites, philanthropists and politicians.

Washington essentially encouraged Black people to work hard and keep their heads down so as to gain the acceptance of whites. He authored more than a dozen books, one of which Up From Slavery, quickly became a best-seller. With Washington at its helm, Tuskegee University grew into a million dollar institution that was home to another lauded historical figure, George Washington Carver, one of the brightest inventors, scientist and agriculturalists in history.

Washington led Tuskegee until his death in 1915.

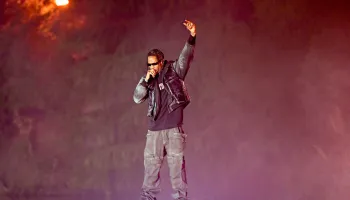

Source: Education Images/UIG / Getty

Decades earlier, in 1895, Washington gave a speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. Speaking to a mostly white audience in what became known as the “Atlanta Compromise,” Washington stated that Blacks should to get used to racism and put their energy towards “economic self-improvement.”

In the speech, Washington made a plea to the white audience, “Casting down your bucket among my people, helping and encouraging them as you are doing on these grounds, and to education of head, hand, and heart, you will find that they will buy your surplus land, make blossom the waste places in your fields, and run your factories.

“While doing this, you can be sure in the future, as in the past, that you and your families will be surrounded by the most patient, faithful, law-abiding, and un-resentful people that the world has seen,” said Washington. “As we have proved our loyalty to you in the past, in nursing your children, watching by the sick-bed of your mothers and fathers, and often following them with tear-dimmed eyes to their graves. In the future, in our humble way, we shall stand by you with a devotion that no foreigner can approach, ready to lay down our lives, if need be, in defense of yours, interlacing our industrial, commercial, civil, and religious life with yours in a way that shall make the interests of both races one. In all things that are purely social we can be as separate as the fingers, yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress.”

His words obviously didn’t sit well with DuBois.

DuBois, a native of Massachusetts was born free. He was a graduate of the University of Berlin and Harvard University (where he became the first Black person to earn a doctorate) and was perhaps one of the most vocal critics of Washington and the “Tuskegee Machine.” He too believed that education was important, but not as a means of assimilation. DuBois helped found the NAACP, he vehemently opposed Washington’s infamous “Atlanta Compromise” and pushed for Blacks to obtain equal rights.

He was a Pan-Africanist, sociologist and activist who also fought to help African countries break free from European rule. DuBois promoted the “talented tenth” theory, to encourage Black men to take on higher education. Writing in a 1903 essay DuBios explained that “the Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men.” DuBois was also regarded for “confronting race, class and gender oppression.”

In what appears to be his final interview before his death in 1963 at age 95, DuBois broke down the fundamental differences between him and Washington. He also revealed that their supposed rivalry wasn’t as contentious as some may have assumed.

“I never thought Washington was a bad man,” DuBois said. “I believed him to be sincere, though wrong. He and I came from different backgrounds. I was born free. Washington was born slave. He felt the lash of an overseer across his back. I was born in Massachusetts, he on a slave plantation in the South. My great-grandfather fought with the Colonial Army in New England in the American Revolution.”

“I had a happy childhood and acceptance in the community. Washington’s childhood was hard,” he continued. “I had many more advantages: Fisk University, Harvard, graduate years in Europe. Washington had little formal schooling. I admired much about him.” DuBois added that when Washington died in 1915, “a lot of people think I died at the same time.”