Source: Paramount+ / Paramount+

HipHopWired sat down and talked with the director and star of the Paramount Plus documentary As We Speak: Rap Music On Trial.

One of the more pressing situations affecting Hip-Hop culture and the communities who love it is the persistent weaponization of rap lyrics in criminal cases throughout the United States and abroad. The most vivid example is the current RICO trial being brought against Young Thug by Fulton County prosecutors in Georgia. Sadly, the general public is still unaware of the scale of these actions by the criminal justice system and its effects – to date, 700 trials have used rap lyrics as evidence since 1990.

Source: Paramount+ / Paramount+

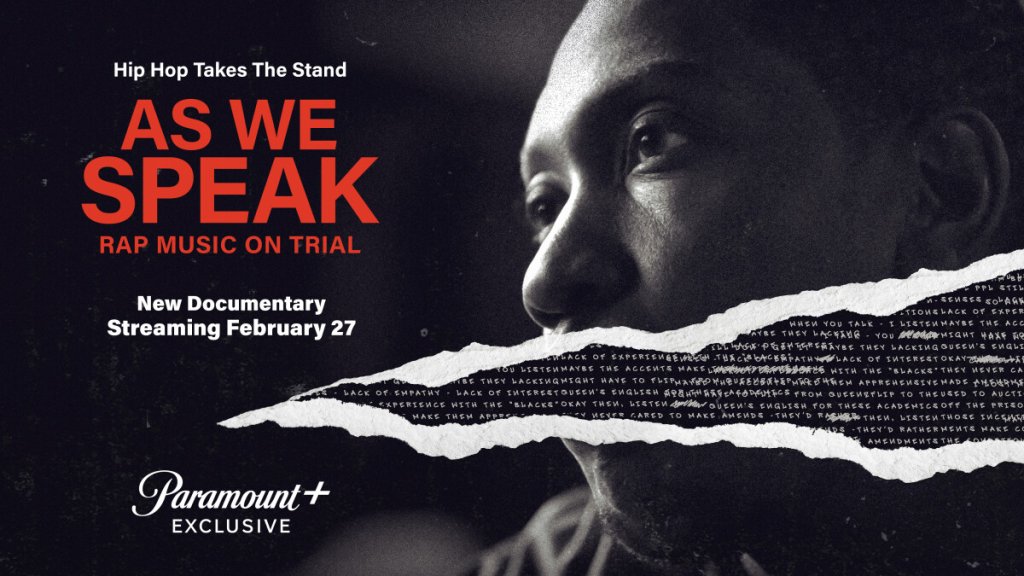

A new documentary, As We Speak: Rap Music on Trial is shining an intense light on how much law enforcement has used rap lyrics to gain convictions in criminal cases. The documentary, which will air on Paramount Plus, is directed and produced by J.M. Harper ((jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, Don’t Go Tellin’ Your Momma). As We Speak is filmed through the perspective of Kemba, a talented MC from the Bronx who is our narrator as he talks with various artists such as Killer Mike, Mac Phipps, Glasses Malone, and attorneys like MSNBC’s Ari Melber across the U.S. and in the United Kingdom about their perspectives in unique ways – even kicking off the film by acquiring a two-way pager to keep his communication private. HipHopWired got the chance to speak exclusively with Harper and Kemba about the film and its message.

HipHopWired: J.M., what was the artistic spark for doing this project? Was it always your intent to get the point of view from somebody who rhymes like Kemba as the main narrator for the project?

J.M. Harper: Really, what we’ve seen with the Young Thug trial especially is, that most of the time this issue is talked about in the national news, and the artist in question is always silent. You don’t hear that they’re told to be silent, they’re made to be silent. And so that was the most obvious entry point for me, was that you could tell the story from the artist’s perspective, and there was just probably something new and interesting to learn there. And something true to learn that that wasn’t being told to us through the D.A. or the prosecutors, or even the news media that was covering it. I knew that Kemba could tell that story with nuance and perspective and do it the way that I had seen some of the great black minds of our time – the great minds of our time, period – but certainly the great black minds of our time who could take something, an issue that seemed one way at first blush, and really articulate it in a way that reached everybody, no matter where you come from. That’s why I thought of Kimba. And I think that’s what he does in the film.

HHW: So Kemba, with doing this film and connecting with some of the other artists that have been under duress, unfortunately, like Mac Phipps – how was it for you to gain more insight into their experiences in talking with them for the film?

Kemba: It was a lot of emotions. Mac Phipps, I have so much respect for, just because he wasn’t upset. He wasn’t bitter. I would definitely be. He just had such an excitement for the rest of his life. You know, in hearing the story…it made me upset. I see why people don’t have faith in the justice system. How somebody could lose 30 years of their life, even when somebody confesses to the crime they get convicted for. How somebody could have their lives twisted against them, a line from this song, a line from that song. It was really unbelievable to hear. And we heard the experiences of a few different people like that, that their art forms are being taken away from them or being used against them. Yeah, it was eye-opening.

HHW: We get a chance in the film to connect with different artists from cities across the globe. What were the most memorable experiences in filming those segments for you both?

Harper: For me, it was Chicago. Just being able to talk to some of the first drill rappers, period. The way that they, 10 or 15 years on, talked about their experience with the labels. Getting 100 grand from a label to talk about what was happening around you. I didn’t know that Chi-raq, Drillinois was a term – I didn’t know about the Driilinois terminology, that it came from the first drill producer. And that term was used on CNN every night around that time. The origin stories of the music, and the complexities there that just hadn’t been spoken about and hadn’t been amplified. I’m sure they were being spoken about, but not until we were able to capture it within this whole context of black history. Could it be sort of put into a context that applies to what’s happening right now in courtrooms? That was one of the most compelling moments of it, every city presented something new. But for me, Chicago was special for that reason.

Kemba: Yeah, I agree about Chicago. I will say Atlanta, just speaking to Killer Mike. And he has a wealth of knowledge. But also, just learning about this. So the history, just to look how far back all this goes, like art being sort of not seen or not considered. Not respected as art. Back from rock and roll to Blues to jazz, back to Negro spirituals, and how this is just the sort of newest iteration of that. That was super surprising to me.

HHW: This is going to be my last question, kind of a little bit on the fun side. Whose idea was it to kick everything off with getting the two-way pager?

Harper: (laughs) So when I was cutting the Kanye jeen-yuhs documentary, which is mostly set in the late 90s, early 2000s, Kanye would always be like writing in the two-way. Two-way this, two-way that. Then I saw that it was all over the place in the music videos around that time and the Hip-Hop community had really embraced a two-way for its short life in between the invention of the pager and the cell phone texting. That became a really interesting starting-off point and then bringing it into the pawn shop was great. Those guys speaking in patois, I didn’t even ask them to talk like that. They asked, “can we say something?” I was like, “yeah” and they just started going off. It was just really organic. This little piece of Hip-Hop history was a perfect vessel for Kemba to be writing and communicating with, thinking that he was off the grid. So, that’s where it came from.

As We Speak: Rap Music On Trial airs on Paramount Plus on February 27.